Imagine a healthcare system that is constructed around people and views health expenditure as an investment in our future rather than a sunk and unrecoverable cost.

Problem Statement

Universal health coverage is a fundamental right for all, and people should have access to the health systems they need, where and when they need them. Healthcare and social systems need to shift to providing preventive services while still providing treatment to individuals and equipping them with the tools required to enable them to take responsibility for their health. One of the main issues identified by IEEPO during and in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic is that nearly half of the countries surveyed perform insufficiently in the provision of universal health coverage.

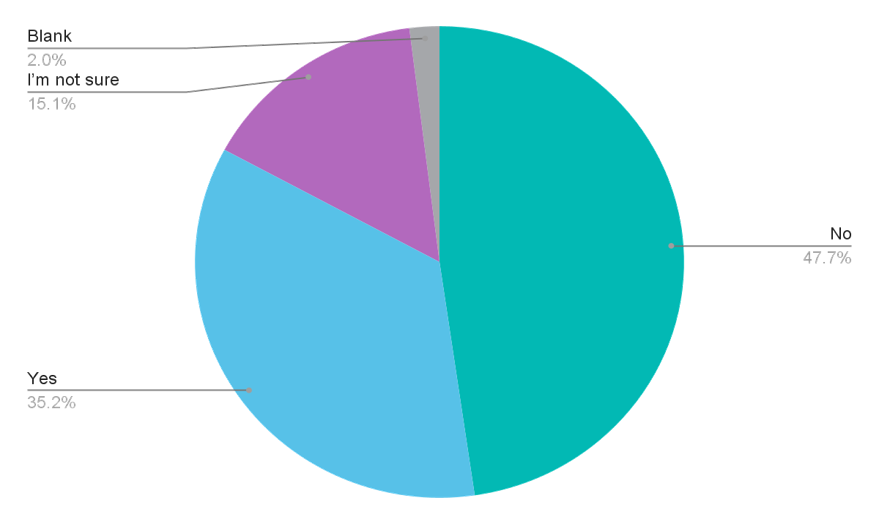

In your opinion, does your country's healthcare system provide universal health coverage?

Discussion Summary

In the IEEPO international patient survey, 47.4% stated that their country’s healthcare system did not provide universal health coverage, and 15.1% were not sure that it did. One of the main reasons for this shortcoming is the separation of primary and secondary healthcare and incomplete communication between them. In a networked and increasingly digital world, it makes little sense to talk separately about primary, secondary and tertiary care - all should be synchronised. They are all part of one system. However, far too many healthcare systems are fragmented and work in silos according to primary and secondary healthcare, or according to disciplines and therapeutic areas (Sperling 2020)

Collaboration between primary and secondary care is not only about the distribution of costs and funding, but also respecting the role of all participants across the healthcare systems.

Humanising primary care means that family doctors (they go by many names: general practitioners, house doctors, primary consultants) should be more involved in healthcare and not just work as administrators and gateways to secondary services.

Governments should be responsible for the synchronisation of care as this is part of the healthcare infrastructure in their countries. Governments are also well positioned to facilitate the necessary cooperation across different stakeholder groups, supported by effective policies. There is a clear need for "human-centred" designs across all healthcare spectrums (including new technologies). This is vital as it can help optimise the patient experience.

The new social contract

The concept of a new social contract based on the acknowledgement, respect and active implementation mainly in the area of personal (health) data has been discussed in the literature for the last decade. IEEPO 2021 contributor and keynote speaker and health science researcher Bogi Eliasen suggests that the clarification and transparency of rights attached to data and their handling requires a new social contract that transcends the current one and spans over national borders (Mitchell, 2021).

While a new social contract may indeed emerge from the processes and developments we see in the collection, processing and usage of health data, this will be a longer process. It’s time for action, to ascertain equality, fairness and transparency. IEEPO contributors argue that the existing human rights framework and the regulations currently in place in several countries and regions of the world provide sufficient leverage to move towards these objectives. Patient communities should drive the discussion around awareness and understanding the importance of the existing social contract and its potential changes. All stakeholders are called upon to consistently respect and apply these frameworks for a humanised approach to healthcare.

Prevention

Healthcare transformation is not feasible without the conscious integration and upscaling of wide primary, secondary and tertiary prevention efforts. The following should be considered:

- Preventable and avoidable illnesses and give people the opportunity to understand their situation and the risks that they face then provide the tools that help them to mitigate risks.

- Some illnesses such as those of genetic origin cannot be prevented, however, their impact can be mitigated. There needs to be awareness in individuals and families about what they can control, and prevent which will, in turn, lead to reduced stress on the healthcare systems, less costs, and better outcomes. Education, awareness raising, dissemination of information, even the provision of nutritional additives can contribute to this objective.

- The need to educate people so they can develop the necessary skills that will help them to avoid harmful behaviours and adopt lifestyle choices to help reduce the likelihood of illness

- Challenges in respect of people who are currently healthy, but who have a specific condition and are using healthcare systems.

Being healthy or unwell isn't black and white, it is not an either-or matter but rather a spectrum that is dynamic and variable across time and culture.

The respondents in the IEEPO global community survey were clear about their preferences regarding prevention and treatment:

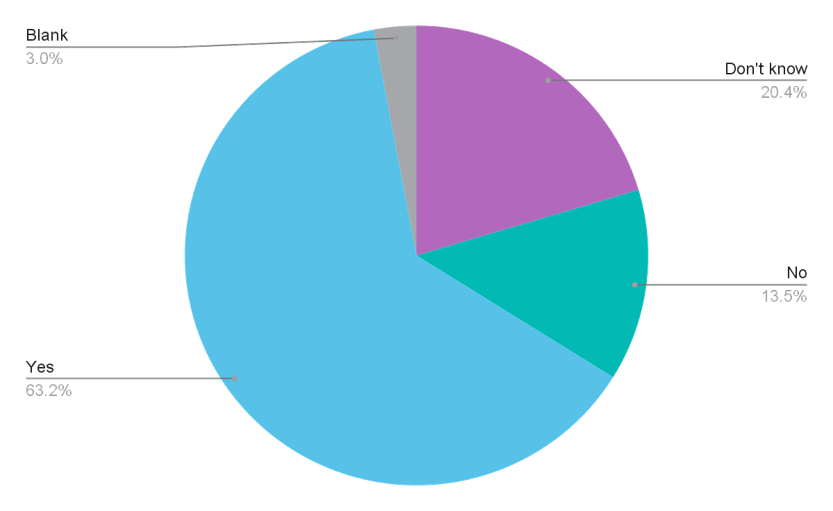

Do you agree with the 50/50 aspiration that half of healthcare budgets should be invested in disease prevention?

63.2% of the respondents agreed that half of healthcare budgets should be invested into prevention, with the other half invested into treatment.

Investment in disease prevention is crucial in a world where patient comorbidities are rising, and populations are ageing. Half of healthcare budgets should be invested in disease prevention and strengthening primary and secondary healthcare systems, with the other half spent on treatment (50/50 model). Healthcare systems face economic resource challenges and pressures in all countries. However, the 50/50 model encourages a shift in mindset to see healthcare spending as a long-term investment in society, rather than a cost to it.

Investment into primary healthcare makes sense

A scoping review by the WHO9 suggests that while there is no clear data yet “primary care can produce a range of economic benefits through its potential to improve health outcomes, health system efficiency and health equity”. The scoping review goes on to suggest a conceptual framework that shows that admissions into secondary healthcare drop, and outcomes improve within stronger primary healthcare settings.

A case needs to be made, in economic terms, to convince policymakers that stronger primary healthcare services make sense economically. Weak primary healthcare results in lost capacity, waste, lack of information, lack of resources, high infant and maternal mortality and declining mental health outcomes.

Consolidation of data

The systematic and careful consolidation of large datasets sitting with different providers under unified principles of data governance can yield better results in primary and secondary healthcare. Integration of primary and secondary healthcare can be facilitated by available data technologies. The increasing digitisation of healthcare, insights gained from big data, and the utilisation of patient-led data generation have already progressed significantly. The use of technology has soared by and this opportunity is explored in greater detail in the chapter “Humanising digital healthcare to build capacity by harnessing the power of patient data”.

The value of big data and the use of sophisticated technologies is to serve the common goals of humanising and democratising healthcare. Social return and value cannot be measured with the usual business metrics, and it is vital that tech technology is deployed as an enabler - not an objective within itself.

Case Study: MAMAtch!: a journey sharing experience - Bringing patients together through technology

Project background and objective

People often feel alone and seek support through dating apps. In Brazil despite there being 66,000 new cases of breast cancer in Brazil in 2020, there was a lack of cancer centered apps in the app store. In order to address this, Femama 10 created an app similar to Tinder to match interest between people who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, to share d oubts, challenges, learning, victories, find support and understand their rights. The app was called MAMAtch! (Mama means ‘breast’ in Brazilian

Activity detail and stakeholders involved.

Once the app was created, the organisation launched the FEMAMA October Pink Campaign in 2018 to drive users to the app. Activity outputs and outcomes By 2020, the app had 1,700 active members registered from more than 70 non governmental organisations around Brazil. Information from tracking behaviour on the app led to an improvement in the understanding of the needs of women living with breast cancer.

Further information: https://www.femama.org.br

Calls to action

1. Governments should be held responsible for driving the synchronisation of care between primary and secondary services to humanise healthcare.

2. All stakeholders should partner under the leadership of the patient community to develop a strong economic argument to drive investments towards primary care with emphasis on prevention and early diagnosis (50/50 model).

3. Patients and citizens should receive much greater support and education on self-care and prevention against the most common chronic conditions. This should include support for campaigns and infrastructure that increase disease awareness, education around screening and early detection, and access to holistic care services.

Link has been copied to clipboard